This story was originally published in the third issue of 34 Orchard in April 2021.

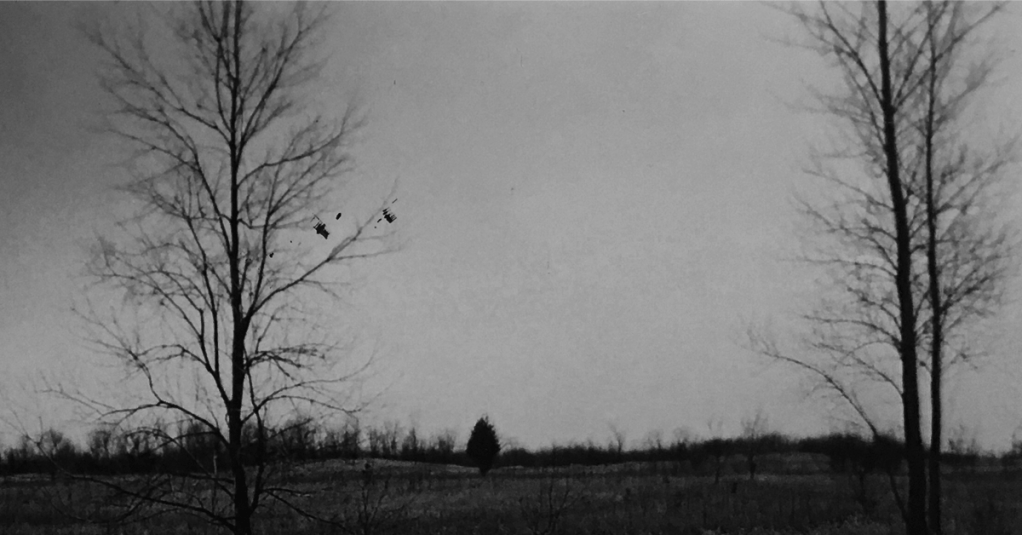

Outside the window bars the night is purple like a bruise. The trees hold this inorganic stillness between their branches, like someone cupping their hands around a firefly so tight you can’t see the light. I long to hear something natural break the silence, like those frogs from the pond behind your mother’s house, where we sat and watched the field blink on and off. I’d settle for a single cicada, although I’m not even sure that it’s a cicada year. Instead, the silence is broken by the audible clunk as someone throws the switch for the floodlights, just outside and above my window. They slowly warm up, illuminating the lawn. Nothing moves beyond the fence. The trees cling to their stillness for another breath. Then Cybil fires off a few rounds from the north watchtower, short cracks from her .22.

The evening has begun.

I’m on day shift, so I’m in my bunk, trying to read, trying not to think about bullets piercing soft skulls. The bullet from a .22 is small, smaller than my fingernail. When it enters the skull it won’t necessarily exit. At least that’s what I saw on some crime show when I was a kid. It’s more likely to ricochet around in a spiderweb pattern, eradicating all of the old neural trails, mangling everything together, shredding memories to ribbons, which expedites a process that our brains already do. When we think of a memory we’re actually recalling the last time that we thought about it. Every time that we recall a memory it damages the original information.

I’m thinking about you again. Rather, I’m recalling the memories I’ve collected of you. They’re the only memories of you, of us that exist anymore, and I don’t know if I want them. They’re too distracting, and that’s dangerous in this world. Maybe if I think about them enough I can damage them so completely that there is nothing left of you in my head. Corroding my thoughts is the closest I can come to changing the past, the only way to make it malleable.

Part of me still wants to believe that we’re only separated by distance. You’re holed up in the top of a warehouse, or in an apartment above a small town grocery store, reading by the light of a candle stub. The door is locked. You have ballpoint pens and a notebook stashed away in a pocket of the bugout bag you made after falling down that rabbit hole of conspiracy theories, and you thought the apocalypse was right around the corner. You were right, but you were a few years too early. Nothing happened in the way that you imagined.

Years and years you carried that bag around, from apartment to apartment, slowly picking it apart. You took the rice out because you were out of rice and didn’t want to walk down to the grocery store. You took all the clothes out when you didn’t have enough quarters for laundry. The notebook got delegated to school. When you needed the bag, you didn’t have it anymore. You weren’t ready, but no one was ready. We found ourselves miles away, walking through the woods after abandoning the car. The highways and interstates were choked and overrun.

We didn’t know where to go, but we had each other. Then I found myself alone. I know you didn’t want to leave, but you were gone just the same. I collected miles that we were supposed to travel together. I collected the names of towns, the ways to survive, the ways to compartmentalize everyday horror. I lived where I could. The foreman’s office in a warehouse. An apartment above a small grocery store. I brought you with me to those places. I left you behind in those places. By the time that I found this community I thought I had left enough of you behind to let go of the past, to start over again.

But I saw you on the fence that day, right before Marcel picked you out from the other watchtower. You were wearing the plaid button down that you bought on our first trip together. We’d gone up north. It was colder than you were expecting, and you didn’t pack properly, even though I told you it was going to be cold. You bought the shirt at a farm supply store. After that it became something like a symbol for us. A shorthand for the memory. I shedded that thought somewhere in the miles, but that goddamned shirt brought it back, a revenant covered in dark blood stains. That tear in your sleeve. Your jeans were urine soaked, and there was mud and shit caked on them. Your boots were worn through from walking on autopilot across broken glass and nails and whatever gutter objects encountered on the travels. I hoped you were shrouded in a cloud, like an obfuscating nebula.

When the bullet entered your brain it scrambled everything into an un-navigable heap of grey stuff. Advertisements. Movies. Piano scales. Books. Vegan restaurants. Photographs. The monotony of brushing your teeth, which were gorestained and rotting. That critical analysis you wrote about the duality of nihilism and hope in Cormac McCarthy’s canon. Arguments. Making love. Talking late into the night about the patterns we saw behind the everydayness of our existence.

I’m thinking about you again, rereading your copy of The Road. There’s an underlined passage:

He’d had this feeling before, beyond the numbness and the dull despair. The world shrinking down about a raw core of parsible entities. The names of things slowly following those things into oblivion. Colors. The names of birds.

All that I have to fill your silence are birds that I can’t name. All of the things I’ve collected, and I can’t name a single one. After an hour they turn off the floodlights. They already drew in most of the moths. Cybil stays up in the watchtower with a pair of night vision goggles. I count her shots. Eventually there will be nothing left to count.

Leave a comment